Chapter 1

PURPOSE OF THE OCP

The purpose of this Official Community Plan (OCP) is to establish policies that guide decisions on community planning and land use management for the Resort Municipality of Whistler (the municipality) over the next five to 10 years and beyond. The OCP also contains a renewed Community Vision for Whistler that articulates the high level aspirations for our resort community, describing what we collectively seek to achieve now and over Whistler’s long-term future. The renewed Community Vision is included within this plan to reinforce the important role of the OCP in pursuing the vision, and to better integrate the vision with supporting municipal policies.

Words that appear in italics are defined in the Definitions section of Chapter 14: Administration and Interpretation. The names of provincial and federal legislation are also italicized.

Our Community Vision is contained in its entirety in Chapter 2; its essence is captured in the following statements:

Whistler: A place where our community thrives, nature is protected and guests are inspired.

- Our resort community thrives on mountain culture and the nature that surrounds us.

- We protect the land – the forests, the lakes and the rivers, and all that they sustain.

- We enjoy a high quality of life in balance with our prosperous tourism economy.

- We seek opportunities for innovation and renewal.

- We recognize the value of our history and the foundations of our resort community.

- We honour those who came before us and respect those who will come after us.

- We move forward with the Lil’wat Nation and Squamish Nation and reconcile with the past.

- We value our relationships and work together as partners and community members.

Municipalities in British Columbia are given the authority to adopt an OCP under the Local Government Act. Additionally, Whistler is required to have an OCP under the Resort Municipality of Whistler Act. As required in the Local Government Act, this plan addresses land use, infrastructure, housing, natural hazards, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions targets, preservation of environmentally sensitive areas, and aggregate (sand and gravel) resources; and contains a regional context statement. This OCP also addresses social and environmental issues and site-specific development controls in the form of development permit area designations and guidelines—content that the Local Government Act indicates municipalities may include in an OCP. Further, this OCP has been extensively updated to recognize and integrate the interests of our First Nations partners in Whistler’s future, in a way that recognizes reconciliation and seeks to achieve our common values and mutual best interests, including the Nations’ economic development interests.

This OCP is a statutory policy document adopted by bylaw that guides the actions of the municipality. All bylaws enacted or works undertaken by municipal Council after adoption of this OCP must be consistent with this OCP. The OCP does not affect existing zoning of land, however, future zoning changes and other bylaw amendments must be consistent with the OCP. Development permit requirements within the OCP have an immediate effect.

Consistent with the desires of the community expressed through the preparation of this OCP, this OCP is not intended to be revised on a frequent basis. However, individual changes may be warranted from time to time, so it must be expected that revision will occur. Like the community, the OCP must be flexible in responding to changing conditions and new community-supported opportunities. To ensure fulfilment of the principles of Whistler’s Community Vision and this plan, the results of this OCP and the relationship of its policies to realities in the community will be routinely measured and monitored using the more than 90 indicators that are tracked on an annual or as available basis. Visit Community Monitoring to view the full list of indicators, performance data and for more information about the program.

Whistler’s OCP was last comprehensively updated in 1993. A new OCP, which has been used as a framework for this OCP, was adopted in 2013 after a comprehensive community planning process. Provincial approval of the 2013 OCP was later struck down by the B.C. Supreme Court, after the court found that the Province’s consultation with First Nations prior to provincial approval of the OCP was inadequate. Since then, the municipality has been working with the Lil’wat Nation, the Squamish Nation and the Province to incorporate principles of reconciliation in the OCP, establish policies for improved working relations, increase the cultural presence of First Nations and consider the Nations’ economic development interests in the future of Whistler. This process has taken time, and in that time the community has continued to evolve and respond to ever-changing external factors. This updated plan builds on the original 2013 OCP update, providing an improved framework for working with the First Nations, and a renewed Community Vision that reflects new current realties and policy directions that have been developed over the past five years.

The OCP at a glance

This OCP is organized in 14 chapters. Chapter 1 provides context and an overview of the community engagement and planning processes that have led to the adoption of this OCP. Chapter 2 provides the Community Vision.

Chapters 3–12 represent specific topic areas that are important to realizing the OCP’s Vision. These chapters provide policy direction intended to guide municipal decisions on specific issues. Each of these chapters is organized into the following sections:

Our Shared Future: What Whistler will look like if the goals, objectives and policies for the chapter are achieved.

Current Reality: What Whistler looks like today, including current issues and opportunities.

Goals, Objectives and Policies: What we seek to achieve and guidance for decision-making.

- Goal: An ideal or condition to be achieved expressed as an end goal or aspiration.

- Objective: Means to achieve a goal or desired result (achievable, measurable and relevant).

- Policy: Specific statements, which guide decision-making; represent clear choices that can be made based on goals and objectives, as well as analysis of pertinent data; may describe standards or measures that should be satisfied.

Chapter 13 designates development permit areas and guidelines intended to regulate development in certain areas and circumstances, such as environmentally sensitive areas, hazard lands or key form and character areas. This chapter aligns with the overall Community Vision in Chapter 2 and policy directions in Chapters 3–12 and will be used to regulate development through the development permit process.

Chapter 14 contains content intended to fulfil legal and administrative requirements. This chapter also contains a glossary of key terms, which are italicized when used in the OCP. These defined terms warrant a unique definition, as they play an important clarifying role in interpreting and administering this OCP.

OCP community engagement process

On April 6, 2010, the OCP update process was launched as Council’s highest post-2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games planning project and the municipality’s first major OCP update since 1993. Community members, partners, visitors, stakeholders, Council and municipal staff participated in a deliberate, community-led engagement process involving over 1,500 participants contributing over 2,500 hours of input to the process. Avenues for participation and feedback included meetings, online questionnaires, workbooks, mapping exercises, interagency referrals, emails, letters, film, art open houses and events, committee review, Council working sessions, and youth events. Thirty-five committed Whistler citizens helped steer this process through The Youth Advisory Group and Community Advisory Group.

The final document was approved by the Province and adopted by Council on May 7, 2013. The OCP fulfilled its purpose as the municipality’s most important planning document until June 4, 2014, when the B.C. Supreme Court overturned the Province’s decision to approve the OCP. As a result of this decision, the OCP’s status reverted back to “third reading” of Council, meaning it had received all the necessary approvals, except for provincial approval and Council’s final approval. As a result, the updated OCP was no longer in effect, and the municipality had to return to using the 1993 OCP, as amended.

Subsequently, the municipality re-engaged with First Nations and the Government of B.C. to revisit the interests of the Squamish Nation and Lil’wat Nation in the OCP. The municipality entered a Memorandum of Understanding with the Province, Squamish Nation and Lil’wat Nation in February 2017, and a Protocol Agreement was signed with the Squamish Nation and Lil’wat Nation in July 2018. As these efforts and ongoing discussions were underway the stage was set for reinitiating the process to adopt an updated OCP. With more than three years of consultation previously completed, Council endorsed a continuation of the 2010–2013 OCP update process on December 19, 2017. This process was undertaken with the following goals: 1) develop and integrate a renewed Community Vision; 2) update the current realities and policies to address factors that have changed since 2013; and 3) integrate ongoing additional engagement with the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations.

Similar engagement methods to those used from 2010 to 2013 were used in the continuation of the OCP update process. Two community forums were held; citizens completed “idea books”, online surveys and “postcards to the future”; and committees and focus groups reviewed and discussed updated OCP content and new information pertinent to the OCP. New engagement tools were also used, including social media engagement, real-time polling and a web-based tool for reviewing and submitting input on the OCP chapters. This significant input added to the 2,500 hours committed from 2010 to 2013.

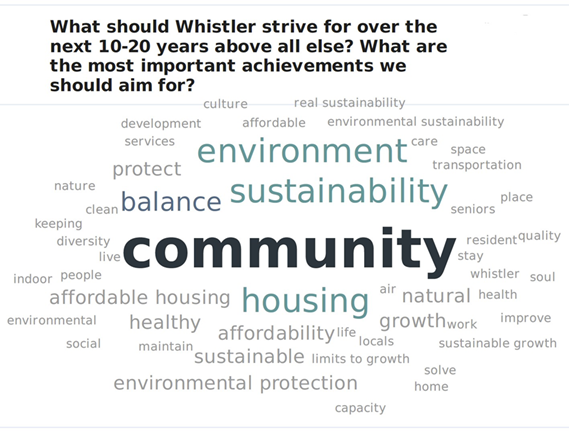

The following images depict the results of online polling that took place at a community forum held during the development of the OCP:

Whistler – A brief history and current context

Whistler is home to nearly 12,000 permanent residents and approximately 4,000 seasonal residents. We are known globally as Host Mountain Resort for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games and as a world-class, year-round mountain resort, hosting over three million visitors annually.

In order to plan our future, it is important to acknowledge where we came from—the history of this place and people—and the current challenges we face. The content below presents brief information on both.

Alta Lake is the high point on an old trail through the Coast Mountains that once connected the Interior with the West Coast. In Whistler, the valley widens and streams feed a chain of lakes surrounded by dense green forests that are rich with wildlife. These lands and waters lie within the unceded territories of the Lil’wat Nation and Squamish Nation, holding historic and cultural traditions. Over thousands of years, the Nations built vibrant, distinct cultures through an intimate relationship with the natural landscape.

The first non-indigenous pioneers to live in the Whistler area arrived in the 1880s. By this point the Pemberton Trail had been completed, connecting Howe Sound through Pemberton to Lillooet and the Interior. The first recreational lodge was built in 1913–1914 by Myrtle and Alex Philip on the western shore of Alta Lake. The Rainbow Lodge was the base for fishing and other summer activities and adventures. Travelling the rugged 120 kilometres north from Vancouver took two-and-a-half days back then, but like those that preceded them and the millions that have followed in their footsteps, it took just one look for them to know they had arrived at a remarkable place. The Pacific Great Eastern Railway began serving the community in 1914 and for the next 50 years, summer tourism and logging formed the backbone of Alta Lake life. Cottages, guest lodges, mills and a few farms clustered around the five lakes and the railroad line.

In 1960, four Vancouver ski enthusiasts sought out to develop a site to host the 1968 Winter Games. London Mountain was deemed a “perfect ski mountain” and renamed Whistler in honour of the whistling marmots that lived among its heights. The Olympic bid failed but Whistler Mountain was developed and opened in 1966 with one gondola, one chairlift and two T-bars. The era of funky A-frames and ski-crazed recreation had begun.

As the area continued to grow, in the mid-1970s an assortment of Whistler community members and stakeholders together developed two visionary initiatives to address the growing needs. First, the valley was incorporated by the Province of British Columbia as a new kind of municipality, a “Resort Municipality,” which elected a mayor and council and developed a master plan to ensure the resort’s ongoing viability, livability and success. Second, Blackcomb Mountain would be developed as a second major ski resort.

The municipality, with the input of both residents and the provincial government, developed the innovative plan for Whistler Village and its pedestrian core that has since been imitated the world over. The idea was to create a town centre full of vitality, situated in visual harmony with its environment, and full of “warm beds” to ensure economic sustainability.

The story of Whistler’s development from the four-bedroom Rainbow Lodge built in 1913–14 to Host Mountain Resort for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games and the community we know today has been told many times and many ways. What is important within this community planning context is that much of what existed before in terms of the spirit of the people and the connection to the natural environment still exists today—the early pioneering spirit has continued as has our deep connection to the natural environment.

Since becoming a highly desirable place to live and a leading destination resort, Whistler has faced a number of ongoing challenges over time. Below is a partial list to highlight some of the key challenges we face and strive to mitigate and adapt to through this OCP and other existing plans and strategies:

- escalating living, housing and business costs;

- pressures to grow and expand Whistler’s physical size;

- climate change impacts on our weather, snowfall and forest fire risk and declining quality and functioning of natural systems;

- uncertain global economic conditions, the changing value of the Canadian dollar and volatile socio-political factors that result in fluctuating visitor numbers;

- increasingly costly limited natural resources such as energy for travel and for operating our amenities and infrastructure;

- growing competition among tourism destinations and changing tourism patterns; and

- changing demographics and population.

Some new or exacerbated challenges are being seen in Whistler more recently. The recent rapid growth in visitation and local population have caused: tension in our community’s social fabric; impacts to natural areas and sometimes the experience we have within them; congestion on our roads and in the Village; increasing GHG emissions; unprecedented increases in market housing prices; and a critical shortage in our housing supply.

These current challenges have been top of mind through the 2018 Vision and OCP update process and shaped the content of both. Each policy chapter contains more detailed information about the current reality.

Moving forward, Whistler is focused on these key priorities: maintaining quality of life for residents; continuing our economic success; achieving ‘balanced resort and community capacity’; building stronger government-to-government relationships with the Squamish Nation and Lil’wat Nation; limiting our development footprint; and protecting the natural environment.

Líl̓wat Nation and Squamish Nation — historical context statements

The statements below were prepared by the Líl̓wat Nation and Squamish Nation, respectively, at the invitation of the municipality. The views expressed therein are not necessarily the views of the municipality.

Since time immemorial the Líl̓wat and Squamish Nations have used, and continue to use, the lands and resources within their respective traditional territories.

Lílwat Historical Context

Líl̓wat people (Lílwat7úl) are the descendants of those who lived throughout the Lílwat Nation Traditional Territory since time immemorial. Lil̓wat Nation territory extends south to Rubble Creek, north to Gates Lake, east to the Upper Stein Valley, and west to the Coast inlets of the Pacific Ocean. The majority of Lil̓wat7úl now reside in Mount Currie.

The Li̓l̓wat have lived in their Traditional Territory for countless generations. Transformers have arrived, battles have been fought, and families have built a history on these lands. Many important sites in the Traditional Territory help to define the history of our people and form the basis for the future. Place names help to identify the traditional uses of areas and the historical significance of sites. The continued existence of ceremonies, legends, historic sites, and transportation and trade routes help to protect the heritage of the Líl̓wat Nation.

The Lil̓wat7u̓l were saved during the great flood by anchoring their canoes to Nséqts (Gunsight Mountain) (located just east of Whistler) and settling below the mountain once the flood waters subsided. Líl̓wat Ancestors occupied several villages, including one at Green Lake, where archaeological evidence of a village site still remains. From that village, Lil̓wat7úl living at Green Lake hunted the upland areas, sometimes travelling west to the headwaters of the Cheakamus and Squamish rivers, and occasionally venturing beyond to the source waters of other coastal streams. After the smallpox epidemics devastated the Lil̓wat7úl living at Green Lake in the late 1850s, the few remaining people joined their families in the villages of the Pemberton Valley.

The Whistler-area remained part of an important trade and travel route. Many traditional food and other products, such as goat’s hair, goat skins, woven cedar-root baskets and considerable quantities of dried berries of the Traditional Territory, were traded by the Lil̓wat7úl with other nations and later with the immigrant miners, fur traders and settlers. In this way, the Li̓l̓wat way of life became imbedded in the new economy created by the interaction of Indigenous people and Europeans. The route between Pemberton and Howe Sound was one of the most important interior-coastal trading routes in southern British Columbia.

The Lil̓wat7úl continued to use the Whistler-area for traditional purposes including hunting, trapping, gathering, and spiritual practices. Their ability to use the area has been impacted by development and government regulation. As recently as the mid-20th century, several Líl̓wat families lived year-round in logging camps in Whistler, and were employed in the lumber industry. Throughout this time, people continued to draw upon the Whistler-area’s abundant hunting, gathering, fishing and trapping resources, which is reflected in the Líl̓wat place name for the Whistler Creekside area: “Nsqwítsu”, meaning “Rich Area”.

Líl̓wat Elders have identified a number of species that were hunted in the Whistler-area including geese, beaver, yellow-bellied marmot, bear, mountain goat, and deer. Lil̓wat7úl trapped at Singing Pass/Fitzsimmons Creek, Rainbow Valley and Rainbow Lake, and Wedge Creek from the turn of the century and into the 1940s. Some trappers continued to run winter traplines under the ski lifts into the 1970s.

Government policies over the years have systematically stripped Líl̓wat, and other First Nations, of their land, rights and resources. Our Ancestors were increasingly disenfranchised and confined to the Indian Reserve Lands in Mount Currie. Today, our population is growing and the recognition of our rights and title to our land is increasing. We, the people of Líl̓wat Nation, are firmly connected to the Whistler-area and see this part of our Territory as integral to who we are as Lil̓wat7úl.

Squamish (“Skwxwú7mesh”) Historical Context

The Skwxwú7mesh people’s territory extends from Point Grey in the southwest, Port Moody to the southeast, to the Elaho River headwaters in the northwest, Whistler in the northeast, and all the islands of the Howe Sound. United by a shared history and culture, the Skwxwú7mesh people have lived within its territory, alongside their indigenous neighbors, since time immemorial.

The upper portion of Skwxwú7mesh territory has been of central importance in Skwxwú7mesh history. Many of the place names in the region record sites of transformation and power, and many of these are places where Skwxwú7mesh people went, and still go, to train for spiritual power. Of particular importance to the Skwxwú7mesh are those sacred sites identified by their connection with the four transformer brothers (Xaay Xays) including the siy’am at the head of the Cheakamus River canyon where a wasteful fisherman was turned to stone to serve as a lesson to others.

It was at Mount Garibaldi, the tallest peak in the region, where the Skwxwú7mesh people had tied their canoe to survive the Great Flood. Black Tusk and Mount Cayley are the two resting places of the Thunderbird. And it was at Rubble Creek where the Thunderbird, who, tired of listening to the people squabble, flapped his wings thus causing the rock face to crash down and bury the village of Spo7ez at the mouth of the creek – a place still considered a sacred area and a refuge for wildlife. These early Skwxwú7mesh people occupied several villages along the Squamish and Cheakamus Rivers, both locations ideally suited for the harvesting of salmon each year. It was from here that the Skwxwú7mesh people moved from mountain to mountain harvesting berries, medicinal and other plants. The mountains became a source of valuable resources including the hunting of ungulates, particularly mountain goats and as a place to collect source rock material for tool making and trade.

It was as early as the 1850s that Skwxwú7mesh members were documented along the Squamish River and soon afterwards Skwxwú7mesh men guided surveyors along “Indian trails” coming from Lillooet Lake down to the Squamish River. Skwxwú7mesh Elders have continued to identify routes that were travelled from Squamish to Mount Currie; these trails signify the importance of the valley for trade and commerce between the Lil’wat and the Skwxwú7mesh.

Skwxwú7mesh members continue to use the Whistler/Blackcomb area for trapping, hunting, fishing, plant gathering, trading and travelling. The slopes along the west side of Highway 99 from Callaghan Creek to Whistler provide Skwxwú7mesh members with berries for sustenance and cedar bark for cultural purposes. Most recently, attempts have been made to protect five Wild Spirit Places, as well as numerous other cultural and spiritual areas, the last untouched wilderness spaces left in the area. This effort is to allow Skwxwú7mesh to pass along their teachings for generations to come.

The Skwxwú7mesh have been negatively impacted by recent developments in the Whistler area, a common hunting ground for grouse and other big game. Archeological sites have been destroyed and fish populations, including salmon and trout, have been impacted by developments along the Cheakamus River and along the Nita, Alpha and Green lakes, most recently by the construction of the Daisy Lake dam and contaminated sewage run-off from Whistler. Use of the Whistler/Blackcomb area by Skwxwú7mesh members for traditional activities has also been hampered by government regulations on hunting, fishing and plant gathering to this very day.

Regional context statement

Whistler lies 140 kilometres north of Vancouver in the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, Canada in the southern portion of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District (SLRD).

Strong, sustained growth is predicted for the SLRD in the next 20 years. Primary factors driving growth include lifestyle choices, increasing demand for recreational services, economic and employment opportunities, natural beauty and environmental qualities, and proximity to the Lower Mainland. Given this projected growth and the associated challenges and opportunities, a collaborative approach to regional growth and land use is essential. This OCP is part of that approach, supporting the Regional Growth Strategy (RGS) to guide development and encourage effective regional collaboration.

The SLRD’s RGS Bylaw 1062, adopted by the SLRD Board on June 28, 2010 and subject to amendments thereafter, is a long-term planning and growth management agreement intended to guide growth and development over a 20- year period. It was developed and approved by the member municipalities in partnership with the SLRD. It provides a long-term vision for the region and identifies and prioritizes goals across the region that meet common social, economic and environmental objectives. With the purpose to “promote human settlement that is socially, economically, and environmentally healthy and that makes efficient use of public facilities and services, land and other resources,” the RGS will guide the SLRD and its member municipalities with respect to land use decisions in accordance with their legislative authority and will be primarily implemented through municipal OCPs and zoning bylaws.

At least once every five years, the SLRD Board is legislatively required to consider whether the RGS must be reviewed for possible amendment. Should the RGS be amended, the regional context statements of member municipalities must be updated within two years as necessary. This Regional Context Statement has been amended to reflect the most recent RGS amendment.

“Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Regional Growth Strategy Bylaw No. 1062, 2008, Amendment Bylaw No. 1872-2024″, was adopted by the SLRD Board on January 29, 2025.

Whistler’s Community Vision, the municipality’s overall approach to growth management, and the goals, objectives and policies presented in this OCP are consistent with the RGS principles and goals.

The RGS articulates eleven goals to strategically address growth management challenges. The goals and objectives of this OCP that correspond to each of the eleven RGS goals are as follows:

Focus Development into Compact, Complete, Sustainable Communities

The overall approach to growth management advocated by this OCP is a focus on enhancing and optimizing existing and approved land use and development primarily within an Urban Development Containment Area. Within that area, the OCP seeks to protect the natural environment, enhance community character and quality of life, make efficient use of existing infrastructure and facilities, strengthen the local economy, and reduce the environmental and energy impacts of the municipality.

Schedule A (Whistler Land Use Map and Designations) establishes the Whistler Urban Development Containment Area (WUDCA), which focuses Whistler’s urban development within the Whistler valley corridor between Cheakamus Crossing and Function Junction to the south, and Emerald Estates to the north, and is consistent with Whistler’s Settlement Area Map (Map 1b) of the RGS. Within this corridor, the OCP seeks to maintain a comprehensive network of natural areas, open space and parks that separate and provide green buffers between developed areas. Residential accommodation, visitor accommodation, commercial, light industrial, institutional and community facilities are directed to be located primarily within the WUDCA.

It is noted that Settlement Areas Maps in the RGS are intended to generally delineate future potential urban development and growth boundaries. Neither the WUDCA nor Whistler’s Settlement Area Map in the RGS are intended to represent areas dedicated exclusively to “urban” development. Within the same boundaries, lands may be designated as protected natural area, non-urban lands, parks and recreation, and similar designations. These lands are not all intended for urban development, but are recognized as generally the main development area within the municipality’s boundaries. The land use designations for these lands are shown on Schedule A.

Conversely, because Whistler is a resort community, based on visitor participation in terrain-based outdoor recreation activities, commercial and tourism-related development may occur outside the WUDCA and the Whistler Settlement Area shown in the RGS. This includes mountain recreation improvements and operations, and auxiliary uses within the Whistler Blackcomb Controlled Recreation Area (CRA) for the Whistler Mountain Resort and Blackcomb Mountain Resort. In some cases, development of these areas may offer opportunities to enhance the participation of First Nations in the resort economy, furthering the RGS goal of enhancing relations with Indigenous communities and First Nations.

In particular, Schedule A of this OCP identifies “Option Sites”, which are lands identified within the provincially approved Whistler Mountain Master Plan Update 2013 as having potential for base area ski developments. There are seven Option Sites that are located within the existing CRA that have potential to add lift staging capacity, new skiing terrain, parking facilities, day skier and commercial facilities, and accommodation. In some cases, these sites are immediately adjacent areas to the WUDCA. In other cases, they are not physically contiguous but they are similarly located within the Whistler valley corridor and their development would be as functionally integrated within the municipality’s core visitor facilities as development within the WUDCA. These sites are all within the area that has been designated by the Province as a Controlled Recreation Area, and have the same valley terrain as other developed portions of the resort. As all of these sites are contained within the existing CRA, and are an extension of existing terrain and facilities connected directly and integrated with the Whistler community, potential development would from a regional perspective be considered consistent with the Goal of the RGS to Focus Development into Compact, Complete, Sustainable Communities. Any proposed development of any of the Option Sites is subject to an OCP amendment and rezoning consistent with the evaluation criteria in Chapter 4: Growth Management of this OCP, which are consistent with the goals of the RGS.

Improve Transportation Linkages and Options

In addition to retaining and reinforcing the existing development pattern to ensure that the viability of public transit use is maintained and improved, this OCP’s goal of prioritizing sustainable transportation methods (e.g., walking, biking and transit) over less sustainable transportation methods (e.g., single occupant automobiles) aligns with RGS policies to increase alternative transportation choices. This OCP also supports regional transit.

Generate a Range of Quality Affordable Housing

This OCP states a goal of housing at least 75 per cent of the local workforce within municipal boundaries and promotes a diversity of housing forms, densities and tenures, including housing that is accessible and affordable.

Achieve a Sustainable Economy

Whistler’s overall approach to growth management seeks to reinforce and sustain the local economy through diversification compatible with tourism and optimal use of existing commercial and light industrial developments; housing the majority of the workforce locally; and supporting sustainable, secure local food systems.

Protect Natural Ecosystem Functioning

Managing the development footprint of the municipality limits negative impacts on the land base through development permit requirements and conditions. The OCP seeks to protect local water quality, reduce energy and water use and GHG emissions, decrease materials used and waste production, manage stormwater and sewer infrastructure to minimize environmental impacts, and maintain a governance structure that is conducive to achieving all of the above.

Encourage the Sustainable Use of Parks and Natural Areas

This OCP affirms the municipality’s, natural setting as being critical to community well-being and the visitor experience. Careful land use planning will help to ensure natural areas are protected and development impacts are limited. Whistler will continue to provide a range of parks, trails and other outdoor recreational opportunities emphasizing viewscapes and a close connection with the natural environment.

Create Healthy and Safe Communities

The objectives in Chapter 8: Health, Safety and Community Well-Being and the transportation, affordable housing and sustainable economy objectives of this OCP complement this goal of the RGS. This OCP articulates goals with respect to local learning opportunities, youth and young adult programs and services, community health and social service facilities, secure local food systems, and a dynamic and unique Whistler cultural identity.

Enhance Relations with Indigenous Communities and First Nations

The municipality, Líl̓wat Nation and Squamish Nation recognize and acknowledge they can best serve their communities by working together in the spirit of reconciliation and cooperation to achieve mutual benefits anchored by common values and interests. This OCP and the renewed process of engagement exemplify the commitment to this spirit. This has been achieved through an enhanced awareness and recognition of respective First Nations and the municipality’s concerns and interests, and formulated through open government-to-government communications. It is recognized that fulfilling this commitment requires an ongoing process of open dialogue and working together in the pursuit of future opportunities. Additionally in support of this commitment, the RMOW recognizes Líl̓wat Nation and Squamish Nation plans and policy documents. This OCP includes a specific chapter dedicated to First Nations reconciliation and has integrated policies throughout the OCP to enhance relations consistent with the goal of the RGS.

Improve Collaboration among Jurisdictions

This OCP contemplates continued cooperation on planning and community development issues among the municipality. Province, First Nations, SLRD, health authorities and other local, regional and provincial organizations and agencies whose mandates and interests intersect with those of the municipality.

Protect and Enhance Food Systems

The goals, objectives and policies primarily in Chapter 8: Health, Safety and Community Well-Being directly support this goal of the RGS. This OCP articulates goals, with supporting objectives and policies, in respect to preserving and enhancing secure local and regional food systems, ensuring dignified access to sufficient, nutritious, affordable and culturally appropriate food, protecting water quality throughout Whistler’s food system, supporting the food system and related activities to enhance the regional economy, and reducing waste from the food system. Additionally, OCP policy supports the SLRD in developing a sustainable food plan that encourages awareness of the expansion of the regional food system.

Take Action on Climate Change

Consistent with the RGS, the OCP states the goal of reducing GHG emissions by 50% below 2007 levels by the year 2030 and reaching net zero emissions by the year 2050. The OCP seeks to support this goal through land use, transportation and solid waste policies. These policies aim to reduce the environmental and energy impacts of residential neighbourhoods, prioritize sustainable transportation, and achieve zero waste. Additionally, specific actions required to reach this goal are guided by the implementation and regular update of the Big Moves Climate Action Implementation Plan (BM CAIP).

Global context statement

Global trends set the context for influencing and shaping the future of resort communities such as Whistler. Climate change and other environmental challenges, economic factors, globalization, social change, wealth inequality, population and demographic changes and technology will present both challenges and opportunities for Whistler in the future. Climate change will affect weather patterns, threatening weather dependent activities and increasing risks of natural hazards such as wildfire, and changing economics and demographics may decrease demand for some of Whistler’s tourism offerings, while increasing demand for others. External factors are likely to escalate the cost of living, housing and doing business in Whistler. Uncertain global economic conditions and volatile socio-political factors have been known to result in fluctuating visitor numbers and there is growing competition among tourism destinations. Technology will revolutionize all industries, shaping how people work, live and play in Whistler and, like social change, will influence visitor expectations. Whistler must continue to adapt and innovate to remain competitive in the global tourism market.

Whistler has an opportunity to be a global leader in sustainable tourism, while continuing to thrive economically by adopting responsible growth management, transportation, land use, and climate change mitigation and adaptation policies. Although it is impossible to prepare for every eventuality, recognizing and adapting to the current realities identified in this OCP, many of which reflect global conditions and trends, will help prepare Whistler for the future. A principled approach allows the municipality to be responsive to both anticipated and unanticipated trends, and effective application of this OCP will allow the municipality to lead global mountain tourism into a successful, low impact future.